By: Eric B. Larson, CEO, Downtown Detroit Partnership

A few months ago, the Downtown Detroit Partnership received funding from the Kresge Foundation to conduct a deep dive into the I-375 Reconnecting Communities project.

If you’re not familiar with the history, in 1959, construction began on this intrastate that cut through Downtown Detroit and destroyed two prominent Black neighborhoods: Black Bottom and Paradise Valley. Even today, most native Detroiters have a family member or know someone affected by the construction of I-375.

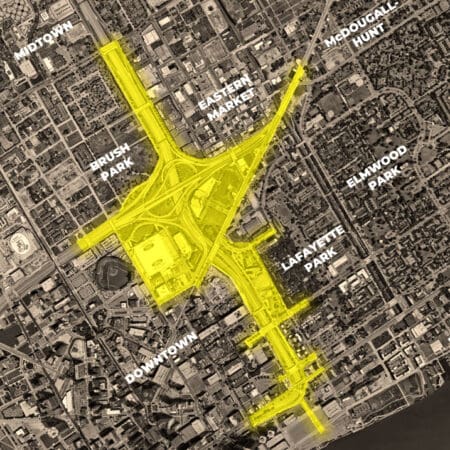

The Reconnecting Communities project is a once-in-a-generation opportunity to address the damage created by I-375 by replacing the highway with a surface street reconnected to the city’s street grid and the Downtown, Eastern Market, Riverfront, and beyond. In addition, it is a transformative opportunity that will set the stage for future neighborhood and business development and create pedestrian- and bike-friendly spaces.

The DDP is a leader in urban transformation, strategic placemaking, and collaborative thinking, and this project requires all that and more. We, along with Kresge, felt strongly that the project required an impartial, third-party review to understand what the community wanted and what the City of Detroit and Michigan Department of Transportation were proposing. We reviewed the latest data and best practices to understand what would benefit Downtown Detroit now and position it for the future.

The DDP retained a nationally recognized consultant team to conduct a Design Peer Review process. The team includes urban american city, Toole Design Group and HR&A Advisors.

First, we developed a set of Guiding Principles that would frame our process.

- Inspire the future of mobility

- Catalyze the market

- Honor, repair, and restore Black Bottom legacy

- Build for a livable + walkable core

- Make sustainable investments

- Practice inclusive participation

Our team has met with Eastern Market Partnership, Greektown Neighborhood Partnership, Lafayette Park residents, sports and entertainment district stakeholders and property owners, and small and large businesses to better understand their interests, concerns, and aspirations for the project.

We also looked at other national projects to understand what worked well (or did not work well) in their respective regions, including:

Milwaukee-Park East Corridor: The city restored the urban grid that was there. This is a good example of a project motivated by grassroots resistance to the freeway and supported by the mayor.

Inner Loop-Rochester: This depressed freeway was brought back to grade and physically connected back to the original street grid. The resulting boulevard is still quite large, and there are still community concerns about pedestrian safety. For this project, they started with one section of the inner loop and plan to remove the rest of the highway in the coming years.

Chattanooga Riverfront Parkway: This is a good example of restoring connection to Chattanooga’s riverfront amenities, providing better connectivity to the Downtown.

I-59 Akron: A great example of what happens when there is engagement around community healing and visioning to begin a restorative process with residents.

I-55 Minneapolis: Another great example of a community-led restorative visioning process.

Finally, as part of the Peer Review, we made a line-by-line review of MDOT’s designs and we are developing a vision for how this project could inform future land use and development. The new infrastructure will shape the Downtown for the next 60 years, just as the I-375 interchange has shaped the Downtown for the last 60 years.

Our last step will be to share our findings, and this will come shortly.

We commend the City of Detroit and MDOT for moving forward with a project to restore these severed connections and further a project that could have a transformational impact on Detroit. It is now up to all of us to ensure we execute a plan that is in the best interest of Detroit’s residents, businesses and future.